THE DIRT BENEATH OUR FEET IS OFTEN TAKEN FOR GRANTED, YET IT’S STILL A PRECIOUS RESOURCE. Approximately one-third of the earth’s soils are already degraded from over-tilling, pollution and over-planting — and with more than 7.5 billion people relying on terra firma for food, soil degradation has become a critical issue.

So how can we reverse this trend and replenish our land?

“In order to repair or manage anything, first you need to know how it works,” says John Klironomos, a biologist in the Irving K. Barber Faculty of Science (FoS). “In the plant-soil ecosystem there are key ingredients, but like any recipe, the secret of success is about proportions and procedure.”

Klironomos explains that it can be challenging to maintain and sustain a plant or crop over time, since the effects of tilling, adding fertilizer and when and which micro-organisms to add are unclear — especially with our changing environment.

“Many of our agricultural farms and forests are sensitive to climate change,” he says. “A small change in the amount and frequency of rain could mean the difference between a high or low crop yield.”

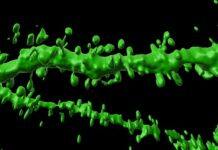

Klironomos is studying how to make plants more resilient to changes in the environment, and believes that fungi in the soil may play a central role. We’re all familiar with the fungi that grow on bread as moulds or those that we consume as mushrooms; however, the fungi that Klironomos and his team are examining form “mycorrhizas” — partnerships with plant roots.

“More than 80 per cent of agricultural plants associate with mycorrhizal fungi,” says Klironomos. “The fungi and the plants depend on each other for survival. This makes them an interesting focus and target for research.”

He adds that the relationship between mycorrhizal fungi and plants is symbiotic: the fungus help plants absorb nutrients, and in turn, plants provide food to the fungi as carbohydrates or sugars.

“Plants take carbon dioxide from the air and, through a process called photosynthesis, turn it into sugar for the plants,” he says. “This is how carbon dioxide levels in the air are reduced by plants. But, it’s a tightly managed system and can easily go off track.”

Klironomos is examining how fungi keep plants resistant to change, even when factors like temperature or water are altered. It’s already known that some fungi are more adaptable than others to these changes, but determining which fungi provide the best protection is one of the research team’s key questions.

“Anything we can do to help stabilize our plant systems will benefit us all,” Klironomos says. “We need our plants to be productive.”