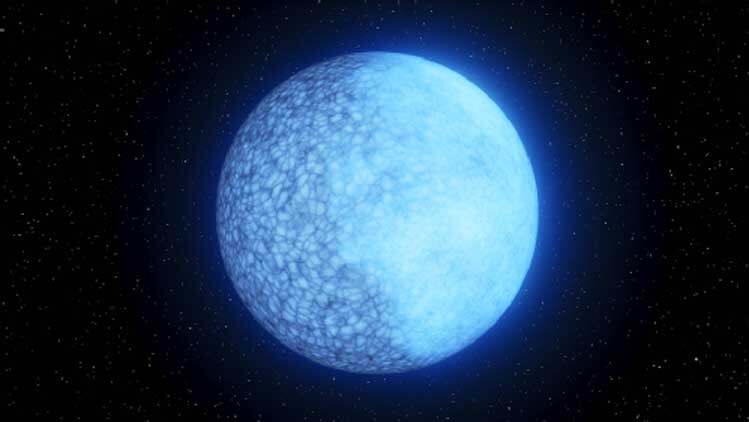

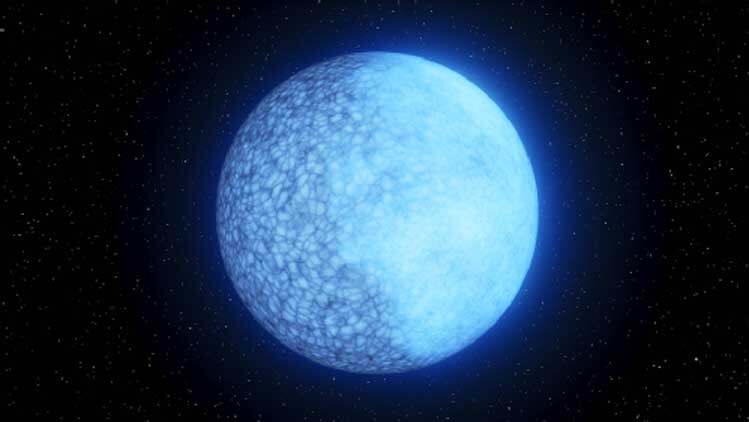

An unusual white dwarf star is made of hydrogen on one side and helium on the other.

In a first for white dwarfs, the burnt-our cores of dead stars, astronomers from institutions including the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) and the University of Warwick have discovered that at least one member of this cosmic family is two faced. The findings, that one side of the white dwarf is composed of hydrogen, while the other is made up of helium, were published today in Nature.

White dwarfs are the scalding remains of stars that were once like our sun. As the stars age, they puff up into red giants, but eventually their outer fluffy material is blown away and their cores contract into dense, fiery-hot white dwarfs. Our sun will evolve into a white dwarf in about 5 billion years.

The newfound white dwarf, nicknamed Janus after the two-faced Roman god of transition, was initially discovered by the Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF), an instrument that scans the skies every night from Caltech’s Palomar Observatory near San Diego.

The team had been searching for highly magnetized white dwarfs, whose origin is still a mystery to astronomy. One candidate object stood out for its rapid changes in brightness, so the scientists decided to investigate further with the CHIMERA (Caltech HIgh-speed Multi-color camERA) instrument at Palomar, as well as the HiPERCAM at the Gran Telescopio Canarias in Spain’s Canary Islands. The data confirmed that the object, Janus, is rotating on its axis every 15 minutes.

Lead author Ilaria Caiazzo, postdoctoral scholar at Caltech, said: “The surface of the white dwarf completely changes from one side to the other. When I show the observations to people, they are blown away.”

Subsequent observations from an observatory atop Maunakea in Hawaiʻi revealed the dramatic double-faced nature of the white dwarf. The team used an instrument called a spectrometer to spread the light of the white dwarf into a rainbow of wavelengths that contain chemical fingerprints. The data revealed the presence of hydrogen when one side of the object was in view (with no signs of helium), and only helium when the other side swung into view.

Co-Author Pier-Emmanuel Tremblay, Department of Physics, University of Warwick, said: “We now know of 350,000 white dwarfs from European Space Agency’s Gaia mission. The two-faced white dwarf is remarkably unique among them all, suggesting that a very finely tuned mechanism can separate hydrogen and helium atoms, based on their mass or electrical charge.”

Scientists are unsure what would cause a white dwarf floating alone in space to have such drastically different faces. The team acknowledges they are baffled but have come up with some possible theories. One idea is that we may be witnessing Janus undergoing a rare phase of white dwarf evolution.

Caiazzo added: “Not all, but some white dwarfs transition from being hydrogen- to helium-dominated on their surface. We might have possibly caught one such white dwarf in the act.”

After white dwarfs are formed, their heavier elements sink to their cores and their lighter elements—hydrogen being the lightest of all—float to the top. But over time, as the white dwarfs cool, the materials are thought to mix together. In some cases, the hydrogen is mixed into the interior and diluted such that helium becomes more prevalent. Janus may embody this transition phase, but it is unknown why the transition happening in such a disjointed way, with one side evolving before the other.

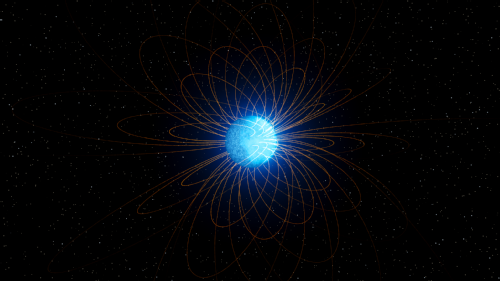

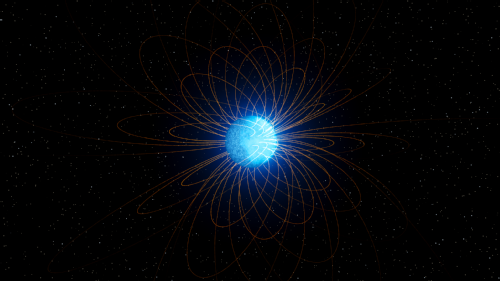

The answer may lie in magnetic fields.

Caiazzo said: “Magnetic fields around cosmic bodies tend to be asymmetric, or stronger on one side. Magnetic fields can prevent the mixing of materials. So, if the magnetic field is stronger on one side, then that side would have less mixing and thus more hydrogen.”

Another theory proposed by the team to explain the two faces also depends on magnetic fields. But in this scenario, the fields are thought to change the pressure and density of the atmospheric gases.

Co-author James Fuller, Professor of Theoretical Astrophysics at Caltech, added: “The magnetic fields may lead to lower gas pressures in the atmosphere, and this may allow a hydrogen ‘ocean’ to form where the magnetic fields are strongest. We don’t know which of these theories are correct, but we can’t think of any other way to explain the asymmetric sides without magnetic fields.”

To help solve the mystery, the team hopes to find more Janus-like white dwarfs with ZTF’s sky survey. ZTF is very good at finding strange objects; future surveys should make finding variable white dwarfs even easier.

The study was funded by Caltech’s Walter Burke Institute for Theoretical Physics, the European Research Council, The Leverhulme Trust, and the United Kingdom’s Science and Technology Facilities Council.