A team of researchers have for the first-time observed changes in the how different parts of the brain interact with each other after a person’s body is immersed in cold water. The findings explain why people often feel more upbeat and alert after swimming outside or taking cold baths.

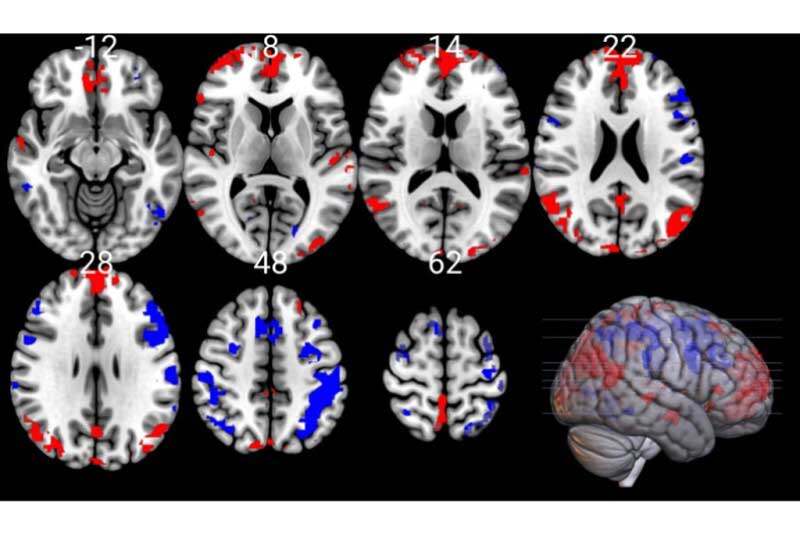

During a research trial, published in the journal Biology, healthy volunteers were given a Functional MRI scan immediately after bathing in cold water. These scans revealed changes in the connectivity between the parts of the brain that process emotions.

“The benefits of cold-water immersion are widely known from previous studies where participants were questioned on how they feel afterwards, but we wanted to see how the shock of going into the cold water actually affects the brain,” explained Dr Ala Yankouskaya, Senior Lecturer in Psychology at Bournemouth University, who led the study.

Dr Yankouskaya’s team, made up of researchers at Bournemouth University, University of Portsmouth and University Hospitals Dorset, recruited 33 volunteers for the trial.

Each participant came to Bournemouth University’s Institute of Medical Imaging and Visualisation where they were given an initial fMRI scan. They were then immersed in a pool of water at 20 degrees Celsius for five minutes whilst an ECG and respiratory equipment measured their bodies’ physiological responses. After being quickly dried they were given a second fMRI scan so the team could look for any changes in their brains’ activity.

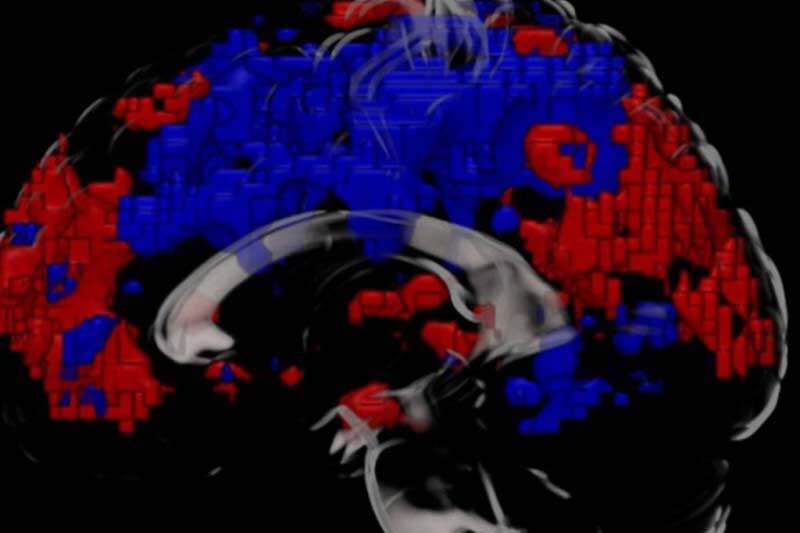

“All tiny parts of brain are connected to each other in a certain pattern when we carry out activities in our day to day lives, so the brain works as a whole.” said Dr Yankouskaya. “After our participants went in the cold water, we saw the physiological effects – such as shivering and heavy breathing. The fMRI scans then showed us how the brain rewires its connectivity to help the person cope with the shock.”

Comparing the scans showed that changes had occurred in the connectivity between specific parts of the brain, in particular, the medial prefrontal cortex and the parietal cortex.

“These are the parts of the brain that control our emotions, and help us stay attentive and make decisions,” Dr Yankouskaya said. “So when the participants told us that they felt more alert, excited and generally better after their cold bath, we expected to see changes to the connectivity between those parts. And that is exactly what we found.”

The team are now planning to use their findings to understand more about the wiring and interactions between parts of the brain for people with mental health conditions.

“The medial prefrontal cortex and parietal cortex have different wiring when people have conditions such as depression and anxiety,” Dr Yankouskaya explained.

“Learning how cold water can rewire these parts of the brain could help us understand why the connectivity is so different for people with these conditions, and hopefully, in the long-term, lead to alternative treatments,” she concluded.