The University of Hull is closing the gender gap when it comes to studying physics – thanks to an inspirational campaign to attract more female students.

While the national percentage of women studying physics is just 22% at degree level – and even less in areas of high deprivation such as the Humber region – at the University of Hull female students account for 45% of the first-year physics class (2021-22).

At the University of Hull, female students account for 45% of the first-year physics class

The University’s Physics degree course is ranked number 7 in the UK (out of 51 providers).*

As leading scientists react to the government’s social mobility commissioner’s claims that girls do not choose physics A-level because they dislike ‘hard maths’, the University’s Changing Face of Physics campaign continues to attract female students to the supportive and welcoming physics community in Hull.

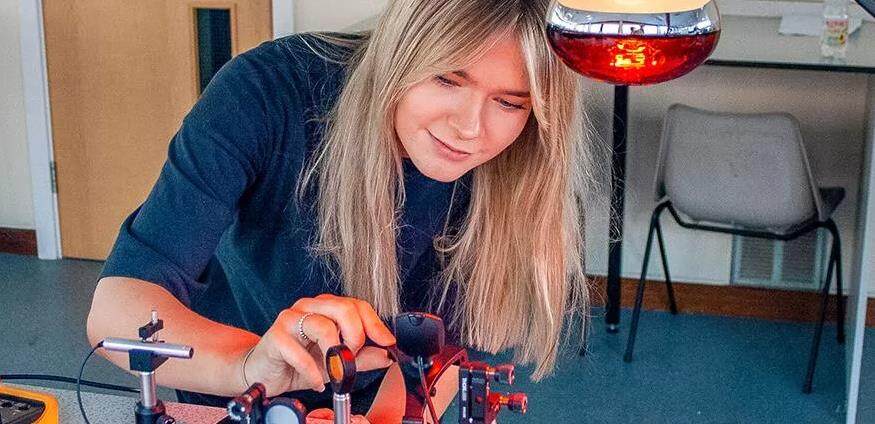

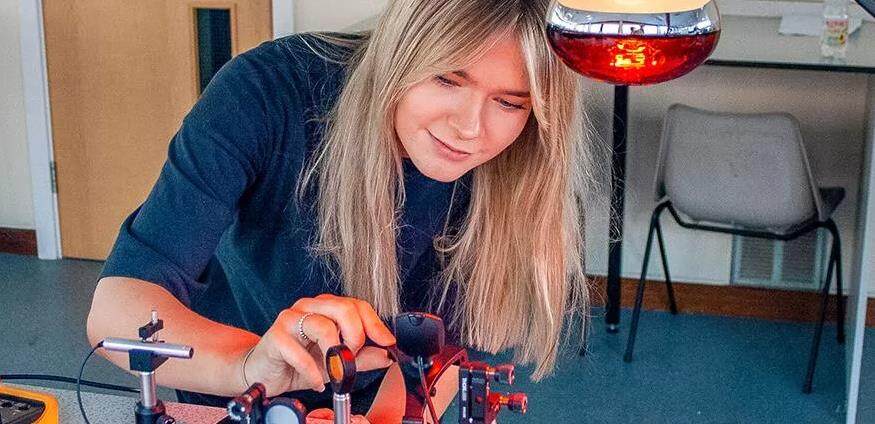

University of Hull postgraduate student Kate Womack, who came to Hull to study for a BSc Physics and Astrophysics and MSc (Research) Physics, said: “Campaigns like Changing Face of Physics and Breaking Barriers are incredibly important.

You can read more about Kate’s story at the end of this article.

Professor Brad Gibson is the inspiration behind the campaign, Head of the University’s Department of Physics & Mathematics, Director of the E.A. Milne Centre for Astrophysics and dedicated to raising aspirations for pupils and students in the region. He said: “We believe 45% to be the highest fraction of women in first year physics classes within universities in the UK.

“There has been a lot of coverage in the media recently about Katharine Birbalsingh’s comments to MPs and the under-representation of women in physics. Her generalised statements that women do not like ‘hard maths’ do not align with Maths GCSE or A-level results (where girls have outperformed boys of late, and never lagged behind boys regardless), and they do not align with our experiences at Hull.

Ten years ago, female students accounted for 12% of physics student at the University of Hull. Five years ago this rose to 25%, as a result of the impact of the Changing Face of Physics campaign, a recruitment campaign that encouraged female students to think again about a career-path in physics and not to be deterred by any preconceptions.

At present, the figure is 28% for female students across all five years of the degree course. Prior to 2016, uptake was between 10-14% in the Hull region.

The context of female under-representation when it comes to studying physics has been well documented: In 2018, New Scientist reported that in 2016 no girls studied A-level physics in almost half of the schools in England that admit girls. In the same year (2016), just one-third of schools had two or more girls taking the subject. Back in 2012, an article in The Observer examining ‘Why don’t more girls study physics’ stated that around 17% of girls apply to do physics at undergraduate level, followed by a more substantial decline in the numbers moving into permanent academic jobs – reporting that only 7.9% of these undergraduates were staying on to become senior lecturers and 4% professors.

Writing on the issue in New Scientist (May 2022), Maria Rossini, head of education at the British Science Association, concluded: “If ingrained attitudes about science and misplaced cultural gender stereotypes lead to systemic barriers that dissuade girls from engaging, then, as a community, we need to examine our own attitudes and failings.

“It is time to call out opinions like Birbalsingh’s, and create a learning environment that actively breaks down stereotypes, in order to support girls and other under-represented groups to thrive in STEM subjects.”

University of Hull Physics postgraduate student Kiri Newson, who came to Hull to study BSc Physics and is now a recipient of the Bell Burnell Graduate Scholarship, said: “I think often throughout school, women grow up being told that subjects such as physics are for men and that they’d be better off doing subjects such as biology or English.