A new Te Whare Wānanga o Waitaha | University of Canterbury (UC) study has found the average delay from symptom onset to confirmed diagnosis of endometriosis is more than eight years in Aotearoa New Zealand.

The study, conducted by fourth year UC Mechanical and Biomedical Engineering student Katherine Ellis, is part of a longer-term research project with a goal to introduce an engineering approach to diagnosing and treating endometriosis – a debilitating condition affecting about 120,000 women in Aotearoa New Zealand. The research is supported by UC Engineering Senior Lecturer Dr Deborah Munro and Lecturer Dr Rachael Wood, with seed grant funding from the UC Biomolecular Interaction Centre.

The first stage of this research surveyed 50 endometriosis patients aged 18 to 48, and involved 50 questions, of which 23 were text-based and 27 were quantitative answers. The patients then participated in online discussions.

“Our research is about approaching endometriosis through the lens of engineering problem-solving methods,” says Ellis. “Important to that lens is considering the current status of care for patients, what needs to be improved in their journey through diagnosis and treatment, and what constraints there will be on any solutions designed for them.

“In this study, we found that the average delay from symptom onset to a confirmed diagnosis was eight years, eight months. Following this immense delay, the most common reaction amongst patients (86%) was relief, because now there was a name and an identifiable cause for their symptoms and their pain.”

Ellis says the biggest reason for the delay is that the only way to get a definitive diagnosis is to undergo surgery. Survey results also showed treatment options such as pain relief and hormonal medications were often considered ineffective, but were routinely offered as the first, or only, options for patients.

“Of the 80% of patients who had been prescribed the combined oral contraceptive pill for their endometriosis, only 25% found it an effective treatment, while 84% had had laparoscopic surgery, with 67% finding that effective for their symptoms. Similarly, the use of progesterone-only pills, which are emphasised in the New Zealand endometriosis guidelines, were considered effective for endometriosis treatment by only 24% of users,” she says.

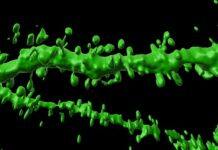

“To get a definitive diagnosis requires examination of the endometriotic tissue removed by laparoscopic surgery and subject it to histological examination. Surgery is expensive, hard for many patients to access and traumatic to the body. We aim to change that by developing a novel means of diagnosing or treating endometriosis with simple, minimally invasive methods. As well as collecting the voices and experiences of those living with endometriosis, we are also working with endometriotic cell lines to understand how they behave under various conditions simulated in the laboratory.

“Our research is about finding ways to let patients know sooner, without surgery, that they have this condition so that they can get effective treatment earlier.”

Ellis is in her fourth year studying a Bachelor of Engineering (Hons) majoring in Mechanical Engineering, with a minor in Biomedical Engineering and a Diploma of Global Humanitarian Engineering. She will start her PhD in January 2023.